AI Testing Skills: The Evolution Beyond RAG and MCP

Dec 23, 2025

Over the last three years, LLMs stopped being “autocomplete that talks” and became something closer to a teammate: AI agents that can explore a repo, run commands, analyse data, and iterate until something works. That shift made Agentic Testing possible. I describe it as testing done by AI agents — not scripts, not humans clicking around, but agents that can reason, act, verify, and report.

This progress came in milestones. Function calling gave models “hands”. RAG gave them “facts”. MCP promised a universal connector for tools. But in real usage, that convenience can come with a tax: tool definitions and schemas bloat prompts and get replayed across turns, burning tokens before the agent does useful work.

Skills are the next step: a practical answer to token waste, the lack of reusable playbooks, and the temptation to shove procedures into RAG (which is better treated as documentation, not how-to). Skills formalise procedural memory with progressive disclosure: load tiny metadata up front, then pull detailed instructions only when they’re actually needed.

In this post, we’ll walk that path (function calling → RAG → MCP → skills), then deep dive into skills (structure + Claude vs Codex usage), and finish with two concrete examples: Anthropic’s open-source webapp-testing skill and a brand-new API-testing skill built from scratch.

Agentic Milestones

Picture the early LLM era as hiring a brilliant theorist… and then locking them in a room with nothing but a keyboard.

They could talk, draft plans, invent APIs, explain architectures, even write convincing pseudocode. But they couldn’t touch anything. No filesystem. No browser. No database. No “run it and see”.

So if you wanted anything resembling a workflow — analyse → decide → act → verify → report — you had to fake it with prompt chaining: break the work into steps, call the model repeatedly, and feed each output into the next prompt. It occasionally worked, but it was brittle in all the ways any multi-step pipeline is brittle:

- one wrong assumption early in the chain cascaded into nonsense later (classic error propagation)

- you added “gates” (programmatic checks) between steps just to keep the chain on the rails

- latency and cost climbed because each “step” was another full model call

- debugging meant figuring out which link in the chain dropped a constraint or quietly invented a detail

The milestones below are basically the story of how we moved from that fragile prompt-chaining world into agents that can reliably do things — not just describe them. The first fix was to give the theorist a pair of hands.

Function calling: teaching language to act

Function Calling (which I covered in detail in How does Playwright MCP work post) is the moment we stopped treating the model as a novelist and started treating it as a coordinator.

Instead of asking the model to describe an action in prose (“now call the API with these parameters”), you offer it a set of tools and it responds with a structured call: call X with arguments Y. Your application executes it deterministically, then returns the result so the agent can decide what to do next.

Conceptually, this is a shift from:

- untyped text I/O (ambiguous, hard to validate) to

- typed intent (JSON arguments constrained by a schema), with execution outside the model

But there’s a hidden cost that matters later: to make good tool choices, the model needs to see tool names, descriptions, and often parameter schemas — and those definitions consume context whenever they’re included.

RAG: teaching language to know

Tool use gave the agent “hands”, but it didn’t fix the bigger truth: a model can be fluent and still be wrong.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) tackles the practical version of that problem by retrieving relevant documents and grounding the answer in that material. The point is simple: the model can reference information outside its training data at inference time.

Conceptually, RAG gives the agent a library card:

- it can look things up (docs, tickets, policies, specs, repositories)

- and then speak with receipts.

The distinction that matters later: RAG is a documentation mechanism. It’s built for retrieving truth, not encoding procedures.

MCP: teaching systems to plug into agents

Once tool use became normal, integration sprawl became the next bottleneck: every agent + every service meant bespoke glue.

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is the “USB-C moment”: an open standard intended to make tool and context integrations reusable across ecosystems. Clients can connect to whatever servers they want, and those servers expose tools, resources, and workflows through a consistent interface, regardless of who built the server.

MCP vs CLI: the token efficiency tax

Here’s the bit that shiny demos often skip: universality can be expensive.

If the model is going to choose between dozens of tools, it needs enough tool definition detail in context to make that choice. Those definitions (and results) take up space, and in multi-turn tool use they can become a significant portion of the prompt budget. Anthropic is blunt about the mechanism: direct tool calls consume context for each definition and result, which becomes a scaling problem as you add more tools and do more steps.

It’s not that MCP must resend “the whole schema every time”, it’s that naïve clients often keep a large tool registry in context (or repeatedly include lots of tool descriptions), so you keep paying for schema-heavy descriptions across turns.

Aside: Why does a CLI often feel “lighter”?

Because a CLI is a small, stable surface area. Discovery is typically on demand (“help”, man pages, file listings), rather than preloading a catalogue of JSON schemas so the model can decide. In other words: the CLI is an interface designed to be remembered, while MCP tool registries are often designed to be described.

This doesn’t make MCP bad. It just means the naïve usage pattern can be a token furnace.

Skills: teaching agents to remember how

Skills are the next step because they address what the previous milestones didn’t:

- Function calling helps the agent

act(execute a task), but doesn’t give it a reusable playbook. - RAG helps the agent

know(retrieve information), but isn’t a great place to store procedures. - MCP helps to

usetools we want to use, but can become context-heavy at scale.

A skill is essentially a packaged playbook: a directory containing a SKILL.md file (with required name and description metadata), plus optional scripts/resources.

The key idea is progressive disclosure:

- at startup, the agent loads only the name and description of each skill

- the full instructions are loaded only when the skill is actually relevant

That’s the architectural answer to the token-tax story: keep discovery cheap; lazy-load the detail.

So the milestone map becomes:

- Function calling = hands

- RAG = library card

- MCP = USB-C port

- Skills = muscle memory / playbooks

And that sets up the real question for the next section: what does a good playbook look like when it has to run inside an agent’s mind — and inside a finite context window?

Skills Deep Dive

Skills solve a very specific “agent scaling” problem. You want repeatable playbooks (procedural knowledge), you don’t want to pay tokens for them unless they’re actually needed, and you want them to be shareable (per user, per repo, per team).

The core design principle is progressive disclosure: load a tiny bit of metadata up front, and pull in the heavy instructions/files only when the agent chooses that skill. Anthropic describes this as preloading name + description for every installed skill, then reading SKILL.md (and any linked files) only when relevant.

Codex does the same: it loads just the name/description at startup, and keeps the body on disk until the skill is activated.

The principle behind it is simple: facts belong in RAG, capabilities belong in tools, procedures belong in skills.

Structure of a Skill

At its simplest, a skill is just a directory with a single file:

my-skill/

SKILL.md

That SKILL.md has two parts:

- YAML frontmatter (the discovery layer — the bit that gets preloaded)

---

name: api-testing

description: >

Generate and run API checks for REST endpoints. Use when the user mentions

HTTP, REST, OpenAPI, swagger, endpoints, contract tests, or postman

collections.

---

- Markdown body (the playbook — only loaded when the skill activates)

# API Testing

## Instructions

1. Identify the endpoints, auth, environments, and data setup.

2. Decide the checks: contract, functional, negative, idempotency, rate limits, etc.

3. Implement the checks using the project’s tooling (or propose the

lightest viable harness).

...

As skills grow, you keep SKILL.md lean and “table-of-contents-like”, and push details into linked files (third level of disclosure). Anthropic explicitly recommends this pattern when a single SKILL.md would become too large or too broad.

Codex documents this exact shape (scripts/, references/, assets/) as the standard convention.

my-skill/

SKILL.md # required

references/ # optional docs (standards,

# runbooks, ADRs)

scripts/ # optional executable helpers

assets/ # optional templates/schemas

Claude Code’s docs show the same idea (extra markdown + scripts/ + templates/) and emphasise that files are read only when needed.

my-skill/

├── SKILL.md (required)

├── reference.md (optional documentation)

├── examples.md (optional examples)

├── scripts/

│ └── helper.py (optional utility)

└── templates/

└── template.txt (optional template)

Claude vs Codex Skills

They share the same underlying shape (a folder + SKILL.md), but day-to-day usage differs in ways that matter in practice.

Where skills live

Claude Code:

- User skills:

~/.claude/skills/ - Repo skills:

.claude/skills/(checked into the repository)

Claude also supports skills delivered via plugins.

Codex:

- User skills:

~/.codex/skills/ - Repo skills:

.codex/skills/(checked into the repository)

Practical difference: both support “personal vs team” scoping, but the folder names differ (~/.claude/skills/ vs ~/.codex/skills/).

How skills trigger

Claude Code:

- Skills are model-invoked: Claude decides to use a skill based on your request and the skill’s description.

- That makes the description field the real trigger surface — you’re teaching Claude when to reach for it.

Codex:

- Supports both:

- Implicit invocation (Codex decides based on the description, similar to Claude Code)

- Explicit invocation (you can select/mention skills via UI affordances like

/skillsor by typing$to reference a skill).

Practical difference: Codex gives you a “manual override” path when you want deterministic behaviour (“use this playbook now”), while Claude Code leans more into autonomous selection.

What the runtime loads (token efficiency by design)

Both systems implement progressive disclosure:

- pre-load only

name+descriptioninto the prompt/system context - load the full

SKILL.mdbody only when the skill is actually used - load extra files only when the skill points to them and they’re needed

Codex is especially explicit: required keys are name and description, and it ignores extra YAML keys; the markdown body stays on disk and isn’t injected unless the skill is invoked.

This is the “anti-MCP-token-waste” story in concrete form: discovery is cheap, detail is lazy-loaded.

Guardrails and permissions

Claude Code supports an allowed-tools frontmatter field to restrict which tools can be used while a skill is active (Claude Code–only).

That matters for testing workflows: you can create “read-only” or “safe mode” skills that can’t mutate repos or environments.

Codex’s public docs focus more on format/scaffolding and the scripts/resources convention; it does ship built-in skills like $skill-creator and $skill-installer to create and distribute skills consistently.

Examples

The fastest way to understand skills is to study a well-designed one. Let’s review an official Anthropic example from GitHub (webapp-testing), then build a similar API testing skill for my awesome-localstack project.

Anthropic webapp-testing skill

Anthropic’s webapp-testing skill is a good reference implementation because it’s explicit about scope and mechanics. It doesn’t invent a new “agent-native” browser abstraction. It standardises on a familiar runtime and makes the agent operate through it:

To test local web applications, write native Python Playwright scripts.

From there, the skill does three practical things: it teaches the agent how to choose an approach, how to stabilise a dynamic UI before acting, and how to keep context usage under control. It matters here because it shows progressive disclosure in practice: procedures live in scripts and examples, so the model doesn’t have to “carry” them in prompt space.

1) It encodes a selection strategy (not just advice).

The SKILL.md includes a concrete decision tree: start by distinguishing static HTML from a dynamic webapp; then, for dynamic apps, check whether the server is already running; if not, the “correct” move is to use the helper rather than improvising.

This is valuable because it turns an ambiguous prompt (“test this app”) into a repeatable branching procedure.

2) It formalises an operational loop for dynamic pages.

For the “server already running” branch, it prescribes a reconnaissance-first loop: navigate, wait for the app to settle, capture evidence, derive selectors from rendered state, then act. In the examples and guidance, waiting for networkidle is treated as a key stabilisation step for JS-heavy apps.

3) It treats token/context as a first-class constraint.

The skill is unusually direct about avoiding context bloat. It tells the agent to treat helper scripts as black boxes and not ingest them unless unavoidable:

Always run scripts with --help first…

It also warns that reading large scripts can “pollute your context window”. This is exactly the “progressive disclosure” philosophy applied at the micro level: run tools; don’t paste tools.

The scripts/with_server.py helper

The skill ships a single helper script, scripts/with_server.py, and leans on it heavily in the “server not running” branch. The intended usage pattern is: pass one or more server start commands with ports, then a -- separator, then the command that runs your Playwright automation. The SKILL.md includes both single- and multi-server invocations (e.g., backend + frontend).

Functionally, with_server.py is doing what you’d otherwise end up re-implementing ad hoc in prompts: start processes, wait until ports are reachable, and ensure teardown happens even when the test fails.

The architectural point is the important one for your post: this is a skill-appropriate extraction. Server orchestration is procedural and deterministic, so it belongs in an executable helper, not as repeated “do these steps” prompt text.

The examples/ directory

The repository also includes an examples/ directory. These files aren’t “documentation”; they’re compact demonstrations of patterns the agent can copy with minimal adaptation.

examples/console_logging.pyshows how to capture browser console output by registering a Playwright console event handler before navigation and collecting messages for later analysis. The example records message type and text, and prints them in real time.

This matters because console logs are one of the fastest ways to turn a flaky “it didn’t work” into a concrete failure signal (JS errors, warnings, blocked requests).

- The same examples set also covers two other practical cases: testing static HTML via

file://URLs, and basic element discovery (buttons/links/inputs) as a reconnaissance step.

Taken together, the skill’s structure is very deliberate: policy + procedure in SKILL.md, deterministic orchestration in scripts/with_server.py, and minimal executable patterns in examples/. That combination is why it works well as a skills showcase: it demonstrates how to keep agent behaviour reliable without inflating every prompt with operational detail.

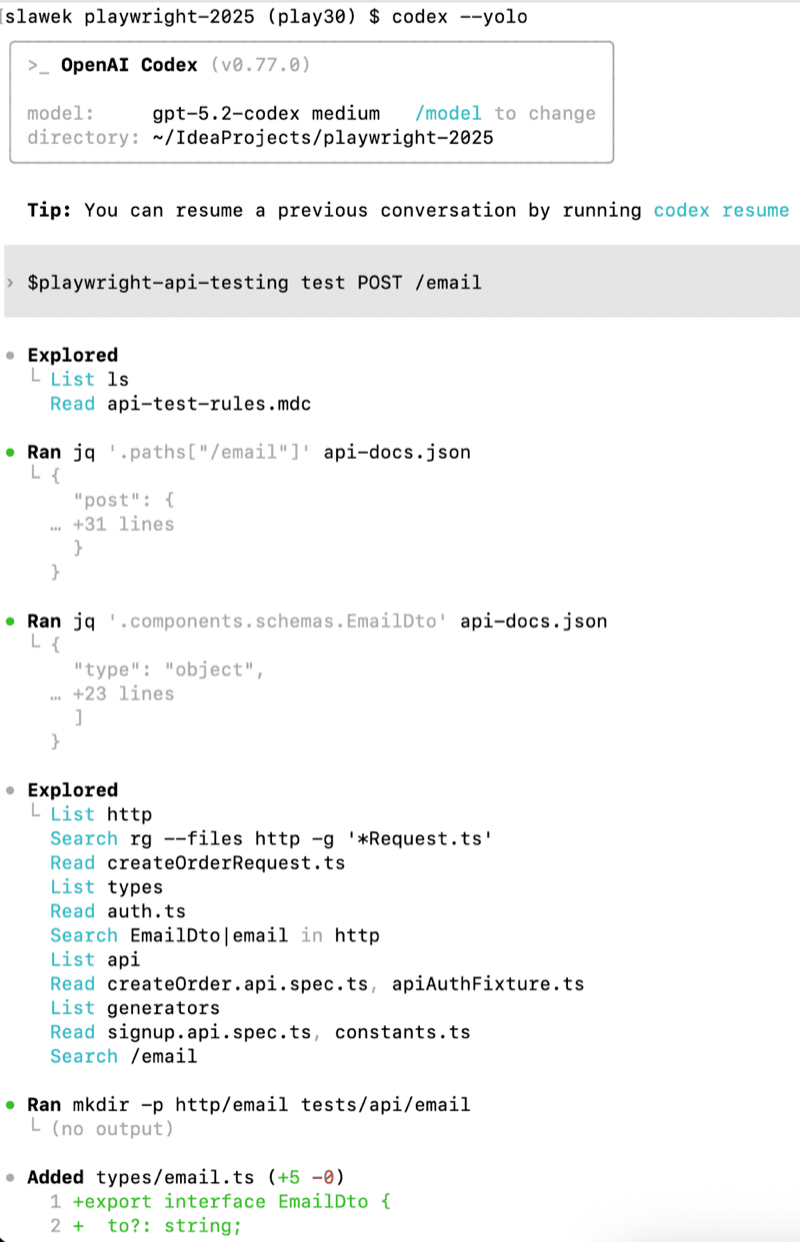

API testing skill for awesome-localstack project

Now let’s put that into practice and create a similar skill for API testing in my awesome-localstack project.

Here’s the resulting SKILL.md:

---

name: playwright-api-testing

description: >

Create, update, and run Playwright API tests in this repository. Use when

the user asks to add or modify API tests, validate API behavior, work with

HTTP clients in `http/`, or follow the repo's API testing rules and fixtures.

---

# Playwright API Testing

## Overview

Use this skill to design and implement API tests with Playwright that follow

the repo's conventions: shared fixtures, HTTP client wrappers, and API test

rules. Validate behavior against `api-docs.json` or live docs at

`http://localhost:4001/v3/api-docs`.

## Workflow

1. Read rules in `.cursor/rules/api-test-rules.mdc` and follow them exactly

(naming, ordering by status code, limited 400s, required lint/test runs).

2. Confirm API schema via `api-docs.json` or

`curl http://localhost:4001/v3/api-docs`.

3. Identify auth needs and obtain tokens using the existing fixtures or login flow.

4. Add or update HTTP client wrappers in `http/` (one method per file, one endpoint per file).

5. Write tests in `tests/api/` using `// given`, `// when`, `// then` comments and shared helpers.

6. Run `npm run test:api` and `npm run lint`, then report failures or regressions.

## Auth and Fixtures

- Use `fixtures/apiAuthFixture.ts` for API tests that need authenticated users.

- `createAuthFixture` signs up a generated user and logs in to return

`{ token, userData }`.

- Bearer tokens come from `/users/signin` responses (`loginResponse.token`).

- Pass tokens via `Authorization: Bearer <token>` in HTTP client wrappers.

## HTTP Client Pattern

- Keep HTTP logic in `http/**` request helpers (one HTTP method per file).

- Use `API_BASE_URL` from `config/constants`.

- Add optional token handling in headers when needed.

- Keep tests thin: tests call helpers; helpers call `http/` clients.

## Test Structure and Data

- Follow `.cursor/rules/api-test-rules.mdc` for naming and test ordering.

- Use Faker-based generators from `generators/` for randomized data.

- Use shared helpers from `tests/helpers/` for products, carts, and orders.

- Avoid duplicating setup logic; extend helpers if needed.

## Validation

- Run `npm run test:api` after finishing API test changes.

- Run `npm run lint` after each incremental change and before reporting results.

- If failures look like app/API behavior changes, report them with the failing

test names and expected vs actual status codes.

## Quick References

- API rules: `.cursor/rules/api-test-rules.mdc`

- API docs: `api-docs.json` or `curl http://localhost:4001/v3/api-docs`

- Fixtures: `fixtures/apiAuthFixture.ts`, `fixtures/createAuthFixture.ts`

- HTTP clients: `http/`

- Example tests: `tests/api/`

To use it, either reference it explicitly with a $ prefix:

Or rely on implicit invocation based on the description:

Both approaches work.

Summary

The agentic shift happened in stages: tool calling turned models from “writers” into systems that can act; RAG helped them stay grounded in reality; MCP made it easier to plug agents into tools. Each step removed friction, but also exposed new constraints — especially around context size, token cost, and the lack of a clean place to store reusable procedures.

That’s where skills fit. They package “how we do things” into lightweight, on-demand playbooks that can be shared and versioned, without stuffing every workflow into prompts or forcing everything into RAG. In practice, skills become a way to make AI agents more repeatable, more token-efficient, and easier to scale as the ecosystem keeps changing.

AI posts archive

- The rise of AI-Driven Development

- From Live Suggestions to Agents: Exploring AI-Powered IDEs

- AI Vibe Coding Notes from the Basement

- How I use AI

- How does Playwright MCP work?

- AI Tooling for Developers Landscape

- Playwright Agentic Coding Tips

- Mermaid Diagrams - When AI Meets Documentation

- AI + Chrome DevTools MCP: Trace, Analyse, Fix Performance

- Test Driven AI Development (TDAID)

- Testing LLM-based Systems

- Building RAG with Gemini File Search

- Playwright MCP Security

- Agentic Testing

- Why AI Coding Is Moving Back to the Terminal (CLI Agents)

- AI Testing Skills: The Evolution Beyond RAG and MCP

Comments on AI Testing Skills: The Evolution Beyond RAG and MCP

Loading comments…