Learning AI

Recent LLM releases such as Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.1 Codex (used via Codex CLI) have once again pushed the boundaries of what we thought possible. These models generate remarkably high-quality code and demonstrate capabilities that would have seemed out of reach not long ago. Combined with modern agentic workflows built on function calling, they can now support — or even automate — almost any engineering task we can imagine, including testing.

Unsurprisingly, companies and organisations have taken notice. There is growing pressure on engineers of every kind to keep up: to experiment, explore new use cases, understand the theory behind these systems, and adopt the practices that allow us to use them effectively. Many employers now expect their teams to stay close to the cutting edge, track breakthroughs, and pay active attention to emerging tools and techniques. Multiple studies proved already that productivity boost isn’t guaranteed, it requires a lot of effort and time to learn and adopt to new tools and techniques.

When I talk to people about AI, I often hear the same concern: the field feels enormous and the amount of information overwhelming. It’s hard to know where to begin — and even harder to know whether you’re learning the right things. That’s why this post is written for everyone: those just starting out, and those who have already begun but may have followed one path too deeply at the expense of others.

A natural question follows: what does it actually mean to “learn AI”? Should you focus on the underlying theory? Should you start by building tools and APIs? Or should you concentrate on using AI effectively in your daily work? Over the past three years — ever since I began exploring the field shortly after ChatGPT’s release — I’ve come to see AI learning as three complementary paths that form a single journey.

In this post, I’ll walk through each of these paths, explain how they fit together, and share how I’ve approached developing my own AI skills. My goal is simple: by the end of this piece, you should know exactly where to focus next and how to continue your AI learning journey with clarity and intent.

The Three Paths of AI Learning

Before diving deeper, it’s worth acknowledging something upfront: learning AI, through software engineering lens, is not a single, linear route. It naturally branches into three distinct paths, each with its own mindset, skill set, and outcomes. The opening image captures this well — three roads that ultimately converge at the same point: becoming genuinely fluent in AI.

The Student Path — understanding how AI works

The Student Path is about learning the fundamentals: how modern models process information, why they behave the way they do, and what the underlying mechanics look like. It starts with the core building blocks — tokens, embeddings, attention, transformers — and extends into the operational systems that surround LLMs today: function calling, tool execution, agent loops, MCP servers, retrieval pipelines, and more.

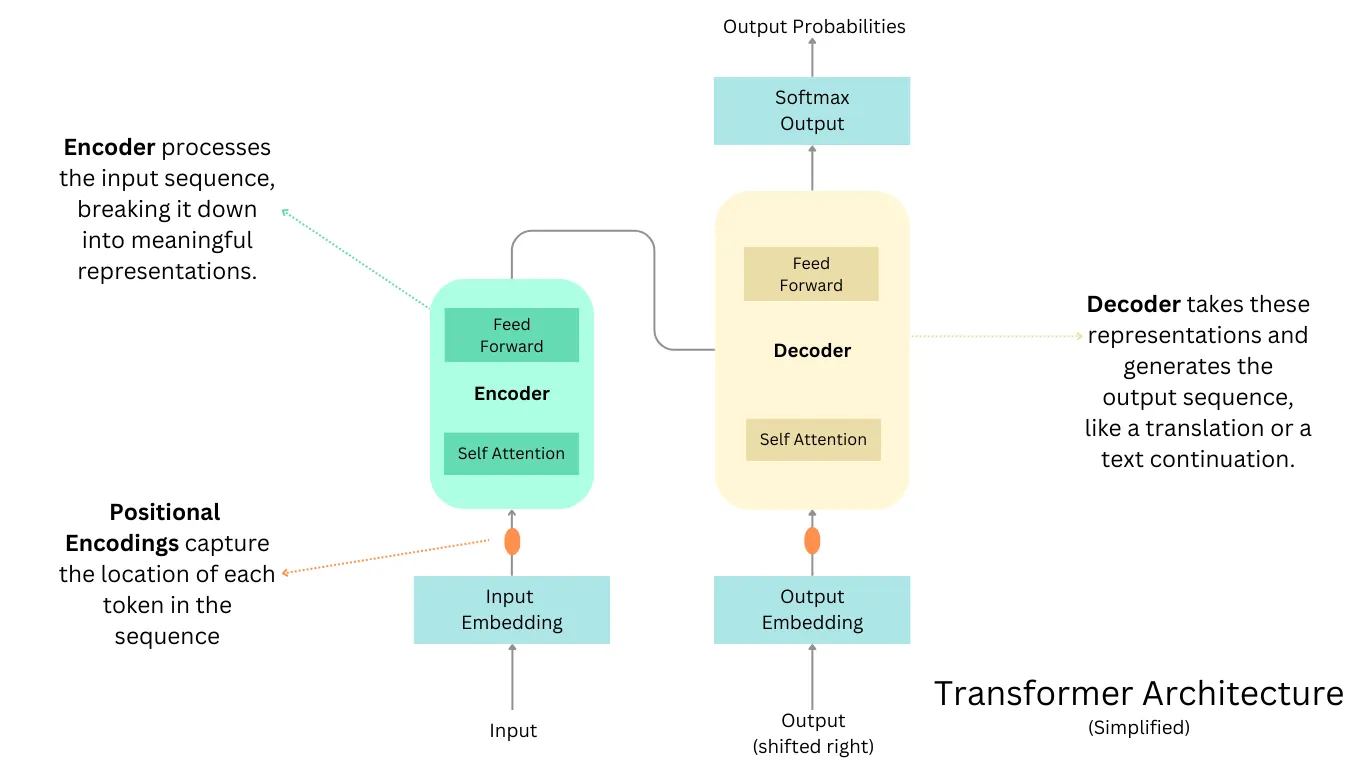

A useful way to begin is with simplified diagrams that make the architecture tangible. For example, The Average Gal offers a clear illustration of the transformer model — the backbone of all modern LLMs. With that mental picture in place, you can gradually unpack the details. What are embeddings? How does attention decide which parts of the input are relevant? Each concept builds on the last.

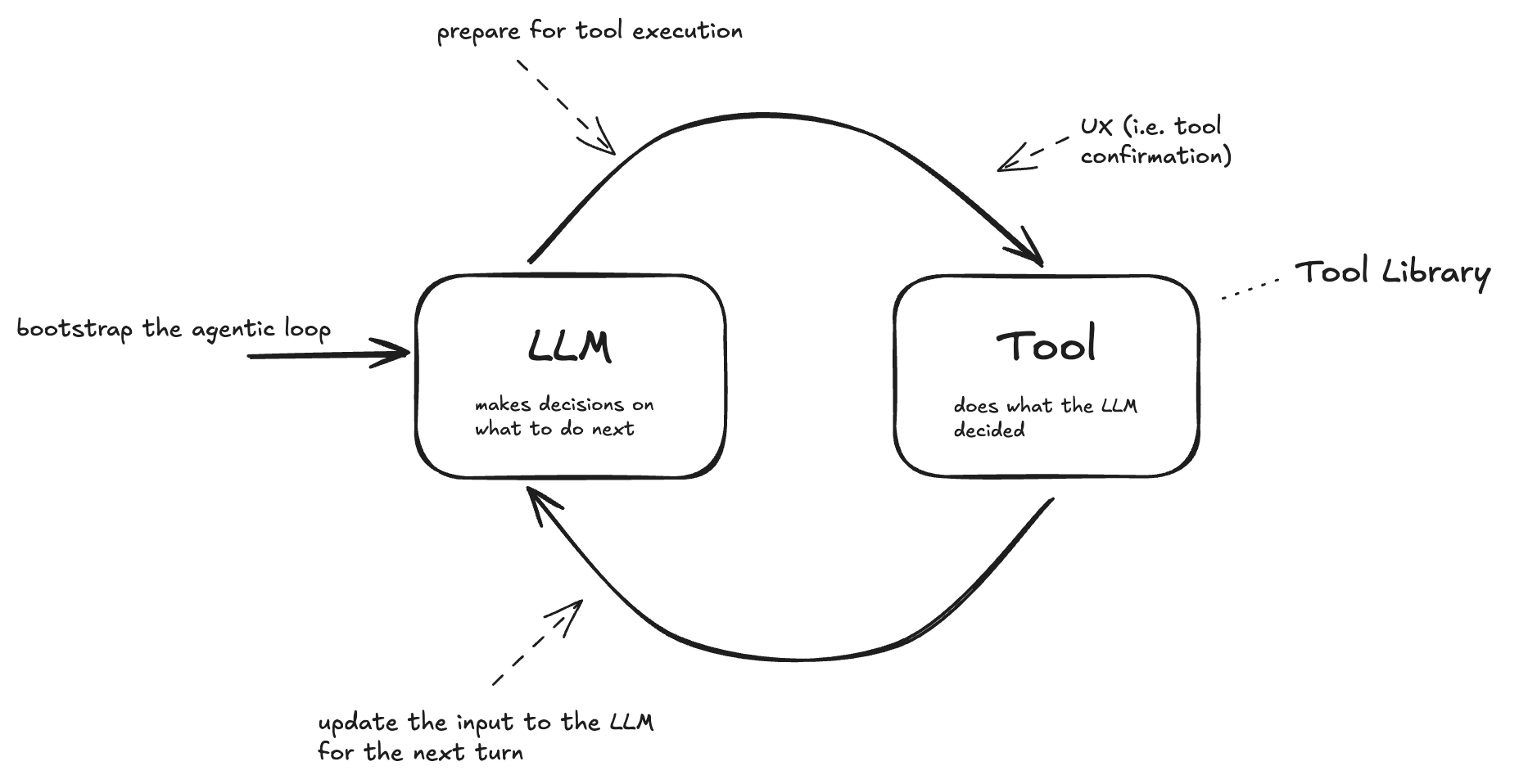

But understanding LLMs alone is no longer enough. Much of today’s AI work sits one layer above the model, in agentic workflows. As authors like Temporal.io point out, agents are essentially LLMs equipped with tools, running inside structured loops. That raises new questions: What exactly is a tool? Why do agents need memory? What problems do MCP servers solve?

This is where the theoretical path becomes truly valuable. Theory lets you imagine what is happening inside the system — it gives you a kind of empathetic reasoning toward the model. You start to appreciate both the strengths and limitations of AI: its ability to repeat structured tasks with perfect consistency, its fluency in writing code or generating documentation, and its persistent weaknesses in social, emotional, and situational reasoning. You immediately understand why agents require full context, why prompting techniques matter so much, and why context engineering is emerging as a discipline in its own right.

And if you choose to go deeper, the layers continue: how attention is computed mathematically, how neural networks represent knowledge, what parameters and weights actually encode, how backpropagation works, how datasets shape behaviour, and how fine-tuning modifies the model.

In other words, the theoretical path is a continuous journey. It begins with the general structure of an LLM, then branches into the execution pipeline, the agent layer, and finally the supporting systems. Piece by piece, all of this starts to connect in your mind.

The Student Path doesn’t require advanced mathematics or a research background. What it does require is curiosity and a willingness to peek under the hood. Even a high-level understanding dramatically improves your ability to reason about the systems you use — and makes every other path in AI far more predictable and far less mysterious.

The User Path — mastering AI in daily work

The second path is the one most closely tied to practical impact. This is the User — the person who brings AI into their day-to-day work and turns theoretical understanding into tangible results. These are the people who know how to integrate LLMs, research assistants, coding copilots, and agents into real workflows rather than just experimenting for experimentation’s sake. Surprisingly, this remains a niche skill, even though organisations increasingly expect their teams to become fluent AI users.

Modern AI tools already allow users to express highly structured, multi-step requests and receive meaningful, actionable output. Deep Research workflows can explore unfamiliar topics, resolve complex questions, or automate hours of investigation. Coding agents can walk a repository, create a plan, and generate coherent patches. Yet despite this sophistication, the User Path is still undervalued. Many companies implicitly assume that employees will simply “figure it out,” even though effective AI use is a skill that improves with deliberate practice, domain knowledge, and experience.

At its core, the User Path is about practical mastery. It’s the ability to use what already exists — powerful pre-built tools, agents, copilots, and APIs — to elevate the work you do every day. Not to build more infrastructure, but to deliver outcomes. In many teams, this is precisely what is missing. Most organisations do not need everyone to write AI wrappers or prototype new agents; they need people who can reliably extract value from the tools that are already available.

Users who excel on this path approach AI with intention. They start with a plan, outline the steps, and break a task into smaller components the system can handle. They iterate, refine prompts, and provide examples when necessary. They know when a problem calls for a capable model versus a cheaper one — perhaps a local model for a lightweight classification task, and something like GPT-5.1 Codex for more complex reasoning or code generation. They understand that LLMs come with cost and latency trade-offs, and they adjust their workflow accordingly.

This path also includes the growing number of people who rely on AI coding tools such as Codex, Cursor, Cloude Code, or repository-level agents. These tools can significantly accelerate software development, analysis, and refactoring — but like all LLM-powered systems, they require substantial infrastructure, which makes them more expensive than traditional tools. That’s simply part of the reality of working with state-of-the-art AI today. Personally, I prefer to invest in these tools over entertainment subscriptions; they provide leverage that compounds over time.

Crucially, strong Users understand why their tools behave the way they do. This is where the Student Path feeds directly into the User Path. A high-level mental model of how LLMs and agents work makes day-to-day usage dramatically more predictable. You instinctively grasp why context matters, why the model forgets information, why structured prompts improve reliability, and when an agent needs explicit instructions versus a free-form task. Theory becomes a practical asset.

In practice, skilled Users are constantly optimising. They test multiple approaches, compare outputs, refine their process, and look for opportunities to improve speed or reliability. They explore what existing agents can already do — rather than building new ones unnecessarily — and integrate those capabilities into their workflow. Their mindset is simple: value first, infrastructure second.

In short, the User Path is about developing the ability to collaborate effectively with AI systems. It is the quickest route to genuine productivity gains, and it naturally prepares you for both the Student and Builder paths. If the goal is to become fluent in AI, this is the most important path to cultivate — and the one most organisations quietly depend on.

The Builder Path — creating tools, systems, and infrastructure

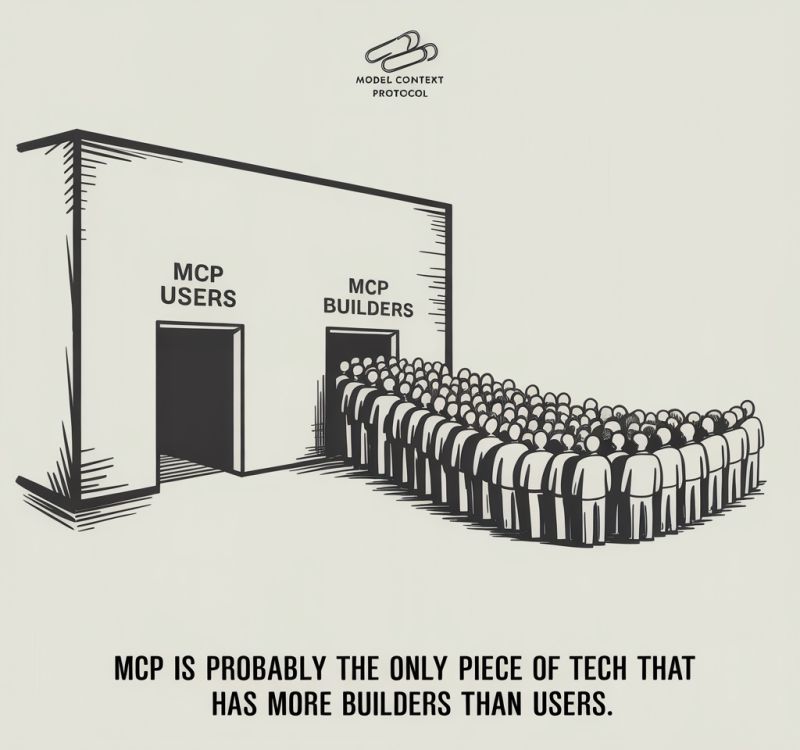

The third path is the Builder — engineers and tinkerers who create applications, agent workflows, integrations, and AI-powered services. It is easily the most glamorised route. Books encourage people to “start building,” managers push for rapid prototypes, and the community routinely celebrates new tools, wrappers, dashboards, and agents. This enthusiasm has produced a remarkable wave of innovation — but also a growing collection of products that are educational, interesting… and often unnecessary. In the MCP ecosystem, there’s even a running joke that there are more people building servers than using them. It’s funny, but not entirely unfair.

Despite the noise, the Builder Path plays a crucial role. It includes the people constructing tooling, frameworks, automation layers, and infrastructure around AI. Some come from machine learning or data-science backgrounds and find this path natural. But you don’t need an ML degree to build AI systems; what you do need is a blend of theoretical understanding and practical engineering judgement.

The moment you move from chat interfaces to APIs, the landscape changes. Suddenly you are the one responsible for designing prompts, injecting system instructions, shaping context windows, deciding when to call tools, handling errors, and managing costs. Many older or lower-level APIs don’t surface system prompts or tool schemas directly — you must construct the whole environment yourself. Effective builders understand how models behave programmatically, not just conversationally. They know that consistency depends on predictable prompting, that memory must be designed, and that every model call has latency and cost implications.

Beyond APIs, many Builders explore MCP servers to expand agent capabilities. Creating a server is not difficult once you understand the protocol, and it can dramatically extend what an agent can do — from interacting with external data sources to orchestrating long-running workflows. Others construct internal RAG systems, build domain-specific tools for their teams, or design new automation layers that thread LLMs through existing company infrastructure.

This path is powerful, but it’s also easy to over-index on. Without a strong grounding in user needs, Builders risk generating wrappers that duplicate existing functionality, agents that don’t deliver meaningful value, or tools that solve problems no one truly has. The best Builders almost always spend a long time as Users first. They understand the friction, the real constraints, and the opportunities worth solving because they’ve experienced them first-hand.

Speaking from experience, building tools — including systems like Gitlab Code Reviewer — has been enormously educational. It reveals how agents think, how context breaks, how prompts fail, and how tools behave under load. But throughout my journey, I’ve tried to remain anchored in the User Path as my primary mode of working. It forces clarity: does this tool genuinely offer value, or is it simply interesting to build?

The Builder Path matters. But it is most effective when built on top of the other two paths. Theory provides the mental models; usage provides the insight; building provides the leverage. When those foundations are in place, you build with intent, not hype — creating systems that genuinely improve workflows rather than adding more noise to an already crowded ecosystem.

Who is actually teaching us about AI?

It’s worth pausing to ask a deceptively simple question: who is shaping the way we learn AI? The answer explains why the User Path — the one most employers quietly depend on — remains consistently overshadowed by the Builder’s path.

Right now, two groups dominate the conversation.

First, the long-established ML community. These are researchers and engineers who understood neural networks long before transformers became mainstream. They know the maths, the training dynamics, the tooling ecosystem. Naturally, they frame AI through a builder’s lens: here’s how the model works, here’s how to construct systems around it, here’s how to train or fine-tune something new. Their perspective is invaluable — but it also biases the educational material towards creation over application.

Second, the early LLM adopters — the programmers who dove in after ChatGPT launched. I’m part of this group. People who got curious, poked at the models, strengthened their theoretical footing, and experimented with agents and automation. Many of them became internal champions in their companies: demonstrating planning prompts, repository-wide refactors, research workflows, and all the tricks that make LLMs feel like leverage instead of novelty. Even here, though, the gravitational pull is similar. With enough tinkering, it’s easy to drift towards building wrappers, tools, or servers — because it is easier than solving real business problems.

I’ve been guilty of this myself, but don’t tell anyone.

Together, these groups produce most of today’s books, blog posts, courses, and talks. Because both groups lean — for different reasons — towards system construction, the User Path is rarely given the attention it deserves.

That imbalance matters. Most organisations don’t need every employee to write an agent framework or implement an MCP server. They need people who can turn existing AI tools into real, business outcomes. People who can plan a workflow, break work into structured steps, validate output, and consistently deliver value with the tools that already exist.

Yet this is precisely the skill set that receives the least structured teaching.

The irony is hard to miss: the most broadly useful path from software engineering perspective is the one least represented in the public learning ecosystem.

The result is predictable. Many professionals assume they must become builders to be “doing AI properly,” when in reality the highest-leverage skill — the one that compounds fastest and benefits the most roles — is becoming a skilled, intentional User. Someone who understands the system well enough to collaborate with it, guide it, and extract consistent value without needing to reinvent its infrastructure.

If the Student Path gives you mental models, and the Builder Path gives you tools, the User Path is where those investments actually pay off — quietly, repeatedly, in the day-to-day work that organisations rely on.

Books

To make sense of the three paths I described earlier, I’ve found it helpful to anchor each one with a book that matches its mindset. This isn’t a random reading list — it’s the sequence I wish I had when I started: understand how these models work, learn how to use them well, and only then look at how to build systems around them.

Hands-On Large Language Models — Student Path

I always suggest starting here. If you want to stop treating LLMs as mysterious black boxes, this book gives you the foundations without burying you in academic jargon. It walks through the mechanics — tokenisation, embeddings, attention, transformers — with just enough depth to give you a mental model that actually sticks.

What I like about it (and what reviewers often point out) is that it manages to make the internals feel tangible. You begin to understand why models behave the way they do, why certain prompts fail, and what “understanding” even means in this context. And once you have that intuition, everything else becomes easier: debugging strange outputs, judging whether a tool is worth using, or even predicting when an agent is about to go off the rails.

Beyond Vibe Coding — User Path

Once the fundamentals land, the next hurdle is figuring out how to use AI effectively in real engineering work. This is where Beyond Vibe Coding shines. It’s the first book I’ve read that treats AI-assisted development seriously but without falling into the trap of pretending AI will replace engineering judgement.

Osmani’s core message resonates with my own experience: AI gives you speed, but speed without structure just accelerates the mess. He spends time on the parts most people gloss over — reviewing AI-generated code, preserving architecture, keeping tests intact, preventing the model from collapsing your entire design into one oversized function. Many reviewers call out how refreshing it is to see someone take this middle ground: enthusiastic about AI, but not naïve about its risks.

This book represents the moment when the User Path becomes intentional. You stop “trying AI tools” and start treating them as part of your workflow — something to collaborate with, not something to hope for.

Vibe Coding — User Path

If Beyond Vibe Coding teaches discipline, Vibe Coding shows the cultural shift happening right now. It’s lively, opinionated, and honest about the chaos that sometimes comes with AI-assisted work — which is exactly why I enjoyed it.

Gene Kim uses an interesting analogy here: in traditional coding, you’re the line cook chopping vegetables. With AI, you become the head chef. You plan the dish, set the tempo, hand tasks to assistants, and refine the results. It’s such a clean way to think about the User Path: not about delegating everything, but about changing the level at which you operate.

What makes the book valuable, though, is its honesty. It doesn’t pretend AI will always deliver clean solutions. It walks through the actual failure cases — disappearing tests, confused refactors, code that looks plausible until it absolutely isn’t. That candour reflects the real state of AI tooling: high leverage, high risk, and highly dependent on the engineer holding the reins.

I see this book as the User Path at full power: confident, experimental, and willing to push boundaries — but grounded in the reality that someone still has to curate, correct, and steer the system.

AI Engineering — Builder Path

After you’ve explored the Student and User perspectives, AI Engineering is the book that brings everything together. It’s the one I reach for when I want a systems-level view — not “how to prompt” or “how to refactor with AI,” but how to build something real that can survive production workloads.

Readers often describe it as the missing manual for modern AI-powered applications, and I agree. It connects the dots between model behaviour and application architecture: when prompting is enough, when fine-tuning earns its cost, how retrieval changes the shape of your system, and how to manage latency, caching, monitoring, versioning, and fallbacks when your core component is probabilistic.

If the Vibe Coding books teach you how to use AI as a multiplier in your daily work, AI Engineering teaches you how to encode that multiplier into a product or platform your whole team can rely on.

This is the Builder Path: not necessary for everyone, but essential if you want to go beyond personal productivity and create durable, scalable AI systems.

Practice

To really understand what LLMs and agents can do — and what they stubbornly refuse to do — you need to walk the User Path and the Builder Path as well. You need your hands on the tools, not just the diagrams.

That’s why I invest in my own learning. I keep active subscriptions: Cursor (where I mostly use Opus 4.5) and Chat GPT Plus (which gives me access to Codex). I also push to use these tools at work — and yes, I’ll say it openly: you should lobby for that too. This is the direction the industry is moving. AI coding isn’t disappearing; it’s evolving. Those who learn to collaborate with AI, rather than fear it or ignore it, will shape what comes next.

I use these tools both at work and at home. I built my entire localstack with Cursor. It lets me experiment without restrictions, run workshops, teach others, and build things on my terms. And because I’ve done the work, people now see me as someone who genuinely understands AI — not someone repeating talking points, but someone who has tested the edges, failed with the tools, iterated, and improved. That reputation alone has opened doors I didn’t expect. It’s also one of the reasons thousands of people read this blog.

So if you’re serious about learning AI: don’t wait for free inference, perfect workplace approval, or the “right moment.” If your company won’t give you access, use the tools at home. Build something small — a script, an agent, a tool in Java, Python, or JavaScript. The stack doesn’t matter. What matters is momentum. The sooner you start using AI, the sooner the theory stops being abstract and starts becoming intuition.

Closing Thoughts

To summarise I’ll borrow the words of AI-guru, Andrej Karpathy:

There are a lot of videos on YouTube/TikTok etc. that give the appearance of education, but if you look closely they are really just entertainment. This is very convenient for everyone involved: the people watching enjoy thinking they are learning (but actually they are just having fun).

Learning is not supposed to be fun. The primary feeling should be that of effort. It should look a lot less like that “10 minute full body” workout from your local digital media creator and a lot more like a serious session at the gym. You want the mental equivalent of sweating.

I find it helpful to explicitly declare your intent up front as a sharp, binary variable in your mind. If you are consuming content: are you trying to be entertained or are you trying to learn? And if you are creating content: are you trying to entertain or are you trying to teach? You’ll go down a different path in each case. Attempts to seek the stuff in between actually clamp to zero.

So for those who actually want to learn. Unless you are trying to learn something narrow and specific, close those tabs with quick blog posts. Close those tabs of “Learn XYZ in 10 minutes”. Consider the opportunity cost of snacking and seek the meal — the textbooks, docs, papers, manuals, longform. Allocate a 4 hour window. Don’t just read, take notes, re-read, re-phrase, process, manipulate, learn.

How to become an expert at a thing:

- Iteratively take on concrete projects and accomplish them depth wise, learning “on demand” (ie don’t learn bottom up breadth wise).

- Teach/summarize everything you learn in your own words.

- Only compare yourself to younger you, never to others.

AI posts archive

- The rise of AI-Driven Development

- From Live Suggestions to Agents: Exploring AI-Powered IDEs

- AI Vibe Coding Notes from the Basement

- How I use AI

- How does Playwright MCP work?

- AI Tooling for Developers Landscape

- Playwright Agentic Coding Tips

- Mermaid Diagrams - When AI Meets Documentation

- AI + Chrome DevTools MCP: Trace, Analyse, Fix Performance

- Test Driven AI Development (TDAID)

- Testing LLM-based Systems

- Building RAG with Gemini File Search

- Playwright MCP Security

- Agentic Testing - The New Testing Approach

- Learning AI

Tags: AI

Categories: AI

Updated: